On August 15th, 2025, the Kenya Gazette published a notice that sent a shockwave through hundreds of property owners in Ruiru.

Gazette Notice No. 11373 was not a routine announcement; it was a legal bombshell. The notice, citing a ruling by the Environmental and Land Court, declared that all subdivisions and titles derived from a 205-hectare parcel known as L.R. No. 11261/76 were null and void. The land, originally belonging to Kangaita Coffee Estate Limited, had been illegally subdivided and sold, leaving hundreds of innocent, third-party buyers with now-worthless title deeds.

For these buyers, many of whom invested their life savings, the notice represented a catastrophic loss. While due diligence is paramount, this situation begs the question: What contractual protection could have shielded these innocent parties from financial ruin? The answer lies in a powerful, yet often misunderstood, legal tool: the indemnity clause.

Understanding Indemnity: A Shield Against Third-Party Risk

Many contracts misuse the concept of indemnity, treating it as a super-remedy for any breach between the two signing parties. However, as legal experts like General Counsel Joanna Valencia explain, its true and original purpose is far more specific and surgical. Valencia notes, “The original role of indemnity was simple: if Party A’s conduct caused Party B to face liability to a third party, Party A should ‘make whole’ Party B.”

She provides the classic and most relevant example: the warranty of title in property law. If I sell you land and it later turns out a third party has a superior legal claim to it, I am obligated to indemnify you against that third party’s claim.

This is precisely the scenario the Ruiru buyers found themselves in. The seller provided a title that appeared valid, but a third party—the original owner, Kangaita Coffee Estate Limited, backed by a court order—emerged with a superior claim that invalidated the transaction entirely.

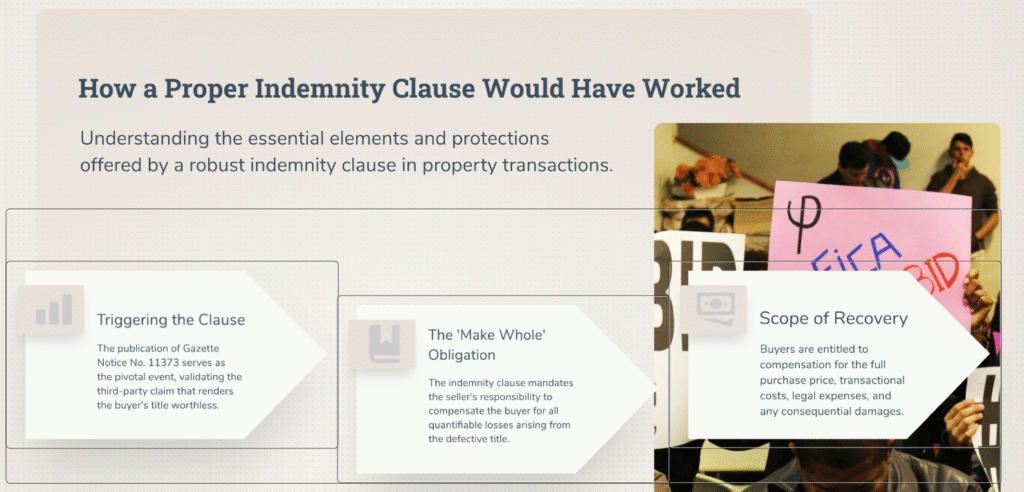

How a Proper Indemnity Clause Would Have Worked

Without a specific indemnity clause, an affected buyer’s only recourse is to sue the seller for breach of contract, a process that can be lengthy, costly, and uncertain. However, a well-drafted indemnity clause in the sale agreement would have provided a more direct and powerful path to recovery.

Consider a hypothetical sale agreement for one of the Ruiru plots. A robust indemnity clause would look something like this:

“The Seller warrants that they possess a good, valid, and marketable title to the Property, free from all encumbrances and adverse claims. The Seller hereby indemnifies, defends, and holds harmless the Purchaser from and against any and all claims, losses, damages, liabilities, legal fees, and expenses arising from or related to any defect in the title, or any claim asserted by a third party challenging the Seller’s ownership or the validity of this title transfer.”

Here’s how this clause would have protected the buyer:

1. Triggering the Clause: The publication of Gazette Notice No. 11373 and the underlying court order serves as the triggering event. The “third-party claim” (from the original landowner) has been validated, and the buyer’s title is now worthless.

2. The “Make Whole” Obligation: The indemnity clause creates a direct contractual obligation for the seller to “make the buyer whole.” This is not just a vague promise; it obligates the seller to cover all quantifiable losses.

3. Scope of Recovery: The buyer could demand compensation for:

(a) The Full Purchase Price: The entire amount paid for the land.

(b) All Transactional Costs: This includes stamp duty, legal fees paid during the purchase, survey fees, and any other costs incurred.

(c) Legal Expenses: The cost of hiring lawyers to defend their now-revoked title or to enforce the indemnity clause itself.

(d) Consequential Damages: Any other demonstrable financial losses directly resulting from the defective title.

Crucially, an indemnity shifts the risk of a defective title squarely onto the shoulders of the seller—the party who was in the best position to know the history and legitimacy of the property they were selling.

The Key Takeaway for Property Buyers

The devastating situation surrounding L.R. No. 11261/76 is a stark reminder that a title deed is not an infallible guarantee. While no contract can prevent fraud, a properly drafted one can provide a powerful financial safety net.

For anyone purchasing land in Kenya, the lessons are clear:

- Go Beyond the Standard Search: Your due diligence must be exhaustive. This includes historical searches to understand the “root of title” and checking for any past or ongoing disputes.

- Insist on a Title Indemnity Clause: An indemnity clause is not an optional extra; it is a fundamental pillar of protection. Do not sign a sale agreement that does not contain a specific, robust clause indemnifying you against third-party title claims.

- Engage an Expert Lawyer: Real estate transactions are complex. A qualified property lawyer will not only conduct due diligence but will ensure your sale agreement contains the necessary protective clauses to shield you from the kind of catastrophic loss faced by the buyers in Ruiru.

Macduff Ronnie

Strategic Legal Partner for Investors & Businesses | Real Estate,